The Timeless Art of Spirit Removal: From Humanity’s Oldest Ghost Drawing to Modern Practice

How a 3,500-Year-Old Mesopotamian Tablet Reveals Millennia of Compassionate Approaches to Spirit Interference Across Cultures

Long before written history, humans likely recognized spirit interference as a cause of suffering and developed methods to address it. While these practices may stretch back tens of thousands of years to our earliest ancestors, the first documented evidence comes from a 3,500-year-old Mesopotamian clay tablet—humanity’s oldest known ghost drawing with accompanying exorcism instructions.

From this ancient starting point through Egyptian healers, Greek soul guides, Japanese mountain ascetics, Hawaiian kahuna, and contemporary energy workers, we can trace a documented history showing humanity’s consistent understanding: some illnesses and disturbances originate not in the body or mind alone, but from interfering spiritual presences.

What has evolved over these documented millennia is not the recognition of the phenomenon, but the approach – shifting from violent expulsion to compassionate guidance, from ritualistic formula to genuine understanding, from warfare metaphors to peaceful transition.

Table of Contents

- The World’s First Ghost: A 3,500-Year-Old Instruction Manual

- Egyptian Spirits and the Art of Sacred Negotiation

- Greek Psychopomps: The Systematization of Soul Guidance

- Japanese Traditions: Dialogue with the Spirit World

- Hawaiian Wisdom: Conversation and Reconciliation

- Jesus and Early Christianity: Simplicity Over Ritual

- Spirit Interference Today: Where Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Understanding

- The Evidence of Continuity

- Conclusion: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Times

- Scientific Sources and References

The World’s First Ghost: A 3,500-Year-Old Instruction Manual

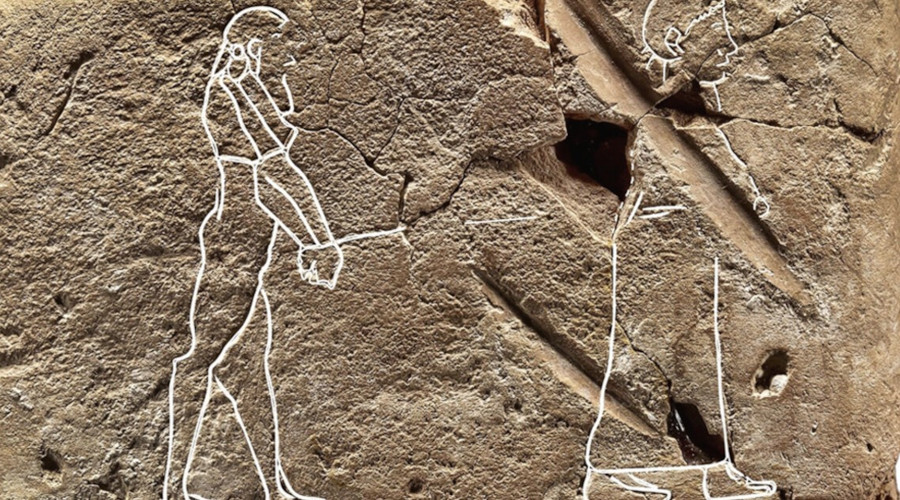

Beneath the ruins of ancient Mesopotamia, archaeologists discovered humanity’s oldest known ghost drawing—a clay tablet that would sit misunderstood in the British Museum (catalog number BM 47817) for over a century after its arrival in 1883. Created by a scribe named Marduk-apla-iddina in the 300s BCE, this tiny fragment preserves rituals dating back to 1500 BCE.

As scholar Moudhy Al-Rashid describes in her book “Between Two Rivers,” one side of the tablet details a ritual for getting rid of “a persistent male ghost who seizes hold of a person and pursues him and cannot be loosed.” The ritual involves making two clay figurines – one of the ghost and one of a woman who can entice him to the land of the dead where he can no longer trouble the living. The other side appears blank “like nothing at all at first sight,” but when hit with light at just the right angle, the clay reveals the shallow lines of two human figures. On the left, a barefoot man with a long beard holds shackled hands before him, attached to a rope. On the right, a woman draped in long garments appears to pull the rope, leading the ghostly figure to eternal life in the Mesopotamian Underworld.

This female figure represents what the ancient Greeks would later call a psychopomp – from the Greek words psyche (soul) and pompos (guide) – literally a “soul guide.” These benevolent entities, whether spirits, angels, deities, or even experienced human practitioners, assist souls in their transition from the world of the living to the realm of the dead. The Mesopotamian solution wasn’t violent banishment but compassionate provision – creating a psychopomp figure to guide the lonely spirit back where it belonged.

The ritual included preparing beer offerings and invoking Shamash, the sun god responsible for guiding souls. The final instruction – “Do not look behind you!” – echoes across cultures, from Orpheus and Eurydice in Greek mythology to Lot’s wife in biblical tradition.

Understanding Mesopotamian Spirit Categories

The ancient Mesopotamians recognized multiple types of troublesome entities:

- Gidim: Ghosts of the dead who remained earthbound

- Utukku: Ambiguous demons that could be beneficial or harmful

- Specialized spirits: Those who died in childbirth, by drowning, or in fires

They understood that spirits remained earthbound when burial rites were incomplete, graves went untended, or death came violently or prematurely—insights that remain relevant in contemporary spiritual practices.

The āšipu – Mesopotamian exorcist-priests – trained for years in temple-schools, mastering not just incantations but also medical knowledge, diagnosis, and even contract law. They were arguably the ancient world’s first integrated medical-spiritual practitioners, understanding that possessing entities often had needs and grievances that required addressing rather than suppression.

Egyptian Spirits and the Art of Sacred Negotiation

Ancient Egyptians inscribed their understanding of spirit interference on temple walls and papyri, viewing it through their cosmic lens of ma’at (order) versus isfet (chaos). They recognized multiple categories of troublesome entities including akhw (the undead), hatayw (night spirits), and various disease demons.

The Bentresh Stela from Karnak reveals their approach: when Princess Bentresh became “seized by a demon,” Pharaoh Ramesses II sent a statue of the god Khonsu. Significantly, the text describes the demon departing peacefully after negotiation, with a celebration feast held for both god and demon. This Egyptian method – dialogue rather than warfare – demonstrates an understanding that spirit problems could be resolved through communication and acknowledgment rather than force.

Egyptian priest-physicians worked from the Per Ankh (House of Life), combining medical knowledge with spiritual practice. Their use of protective amulets and execration rituals shows sophisticated understanding of both prevention and intervention.

Greek Psychopomps: The Systematization of Soul Guidance

The ancient Greeks developed perhaps the most systematic understanding of psychopomps. Their pantheon included numerous soul guides:

- Hermes: The primary psychopomp who guided souls to the river Styx

- Thanatos: Peaceful death personified

- Charon: The ferryman of souls

- Hecate: Goddess of crossroads who helped lost souls find their way

Greeks recognized that souls could become “stuck” between worlds – the ataphoi (unburied) and aoroi (untimely dead). The Eleusinian Mysteries, Greece’s most sacred religious rites, taught initiates that death was a transition requiring guidance rather than a battle requiring victory.

This Greek conceptualization of the psychopomp as compassionate guide rather than violent exorcist represents a crucial evolution in human understanding of spirit work. Whether these guides were gods, spirits, or specially trained humans, their role was facilitation, not force.

Japanese Traditions: Dialogue with the Spirit World

Japanese spiritual traditions developed remarkably nuanced approaches to spirit interference. The medieval yorimashi system reveals sophisticated psychological understanding: rather than immediately attacking a possessing mononoke (vengeful spirit), the exorcist would transfer it into a medium who would give the spirit voice. Through dialogue, the spirit could reveal its identity, grievances, and needs.

Japanese Spirit Categories

Japanese tradition recognized multiple spirit types:

- Yūrei: General ghosts needing help moving on

- Onryō: Vengeful spirits requiring acknowledgment

- Ikiryō: Living spirits projected by intense emotions

- Goryō: Aristocratic spirits requiring appeasement

Even the forceful methods of Shugendō mountain ascetics aimed at liberation rather than destruction – through intense chanting they generated spiritual karma (merit), which they dedicated to the spirits to enable their transition into better realms of existence.

Hawaiian Wisdom: Conversation and Reconciliation

Traditional Hawaiian practices, suppressed by missionaries from 1820 to 1989, preserved profound wisdom about spirit interference. Hawaiians understood spirits could be lost and suffering rather than inherently evil. Their kahuna ho’opi’opi’o (spirit removal specialists) engaged in conversation with the spirit to save the patient – emphasizing relationship over force.

Central to Hawaiian healing was ho’oponopono – family conferences addressing the disharmony that made individuals vulnerable to spirit attachment. Their purification practices like pi kai (ritual seawater sprinkling) weren’t superstitions but practical technologies for energetic hygiene.

Jesus and Early Christianity: Simplicity Over Ritual

Biblical scholarship reveals that exorcism represented approximately 12-21% of Jesus’s recorded healings – significant but a minority. The Gospel writers distinguished between physical healing and spirit removal. Matthew 4:24 states: “They brought to him all who were ill with various diseases, those suffering severe pain, the demon-possessed, the epileptics and the paralyzed” – clearly listing demon possession separately from diseases.

Jesus’s method was revolutionary in its simplicity – direct commands with no ritual paraphernalia, claiming authority through divine relationship rather than magical formulas. This approach contrasts sharply with later Catholic formalization, which reintroduced elaborate rituals, prescribed prayers, and ecclesiastical hierarchy.

Spirit Interference Today: Where Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Understanding

While mainstream medicine largely dismisses spiritual causation, notable exceptions have documented compelling evidence. Dr. Carl Wickland, a psychiatrist and chief psychiatrist at the National Psychopathic Institute of Chicago, spent thirty years researching what he termed “obsessing spirits” as causes of mental and physical illness. His 1924 book “Thirty Years Among the Dead” documents hundreds of cases where patients recovered after spirit removal – cases that had resisted all conventional treatment.

Dr. Wickland’s work, conducted with scientific rigor in hospital settings, demonstrated that many conditions diagnosed as schizophrenia, multiple personality disorder, epilepsy, and various neuroses were actually caused by spirit interference. His wife, Anna Wickland, served as a medium, allowing the interfering spirits to speak and reveal their stories – remarkably similar to the ancient Japanese yorimashi system, though developed independently.

Understanding Different Types of Entities

Contemporary practitioners work with these same principles, recognizing what ancient cultures understood: interfering entities range from confused human souls to genuinely malevolent beings. Lost souls and confused ghosts respond beautifully to compassionate guidance. These beings are often frightened, lonely, or simply don’t realize they’ve died. They need understanding, not warfare.

However, practitioners also acknowledge what every ancient tradition knew: one also encounters entities of genuine malevolence – what various cultures have termed demons, devils, or truly dark forces. While compassion remains the first approach, these cases may require more forceful methods, protective measures, and sometimes the difficult decision to contain or bind rather than release. The ancient Mesopotamians knew this, as did the Egyptians, Greeks, and every culture that developed exorcism practices.

The key insight from both ancient wisdom and modern practice is discernment – knowing which approach fits which situation. Lost human souls need love and guidance, while darker entities may require firm boundaries and stronger methods. Experienced practitioners must be prepared for both, trained in protection and various approaches while never abandoning the compassionate heart that defines ethical spirit work.

Modern practitioners trained in various modalities – from Spirit Releasement Therapy to remote depossession techniques – work as living psychopomps. Not replacing spiritual guides but working alongside them to facilitate peaceful transitions. This role requires extensive training, genuine sensitivity, deep compassion, and the wisdom to know when gentle guidance suffices and when stronger measures become necessary.

→ For detailed information about recognizing symptoms and professional clearing approaches, see: Foreign Energies & Spirit Attachments

The Evidence of Continuity

The persistence of spirit removal practices across cultures and millennia suggests these traditions address genuine phenomena rather than mere superstition. From Mesopotamian āšipu to Hawaiian kahuna to contemporary energy workers, practitioners share core recognitions:

- Some suffering originates from spiritual interference

- Entities have identifiable causes and needs

- Resolution usually requires understanding over force

- Lost souls need compassion; malevolent entities may require stronger methods

- Prevention involves energetic hygiene and psychological health

- Practitioners require extensive training and development

The ancient Mesopotamian provision of a psychopomp for the lonely ghost, Egyptian negotiation with demons, and Hawaiian conversation with spirits all demonstrated this nuanced understanding: most entities deserve help finding their way home, though some may need firm boundaries.

Conclusion: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Times

The history from Mesopotamian clay tablets to contemporary energy medicine reveals consistent human recognition: spirit interference represents a genuine category of suffering requiring specific approaches beyond conventional treatment.

Whether the interfering presence is a lost soul, an unquiet ancestor, an attached entity from trauma, or intentionally sent energies, the wisdom tradition offers hope through appropriate intervention – compassionate when possible, firm when necessary.

The ghost drawn on that ancient clay tablet was shown bound and suffering, being led by a psychopomp to its proper realm. It wasn’t destroyed or condemned but guided home. After three and a half millennia, that remains the highest practice – whether the psychopomp is a deity, a spirit guide, an angel, or a trained human practitioner serving as bridge between worlds.

This ancient wisdom, refined through millennia of practice across cultures, offers profound insights for our modern world: healing comes through appropriate response – compassion for the lost, firmness for the malevolent, and wisdom to know the difference.

Scientific Sources and References

This article is based on peer-reviewed scientific research and authoritative historical sources:

Primary Ancient Sources

- BM 47817 – Babylonian ghost tablet, British Museum, London (c. 300s BCE)

- The Bentresh Stela, Temple of Karnak, Egypt (c. 4th century BCE)

- Udug Hul tablet series – Mesopotamian exorcism texts

- Maqlû ritual texts – Mesopotamian anti-witchcraft rituals

Modern Scholarly Works

- Al-Rashid, Moudhy. Between Two Rivers: A Story of Ancient Mesopotamia. London, 2023.

- Finkel, Irving L. The First Ghosts: Most Ancient of Legacies. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2021.

- Geller, M.J. Healing Magic and Evil Demons: Canonical Udug-hul Incantations. Boston/Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016.

- Konstantopoulos, G.V. “Demons and exorcism in ancient Mesopotamia.” Religion Compass, 14(6), 2020.

- Lucarelli, Rita. “Demons in Ancient Egypt.” Religion Compass, 5(5), 2011.

- Meier, John P. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Volume II: Mentor, Message, and Miracles. New York: Doubleday, 1994.

- Pukui, Mary Kawena. Nānā i ke Kumu (Look to the Source). Honolulu: Queen Liliuokalani Children’s Center, 1972.

- Twelftree, Graham H. Jesus the Exorcist: A Contribution to the Study of the Historical Jesus. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1993.

Medical and Clinical Sources

- Wickland, Carl A., M.D. Thirty Years Among the Dead. Los Angeles: National Psychological Institute, 1924.

- Baldwin, William J. Spirit Releasement Therapy: A Technique Manual. Terra Alta, WV: Headline Books, 1991.

- Hickman, Irene. Remote Depossession. Kirksville, MO: Hickman Systems, 1994.

Additional Resources

- International Association of Exorcists (recognized by Vatican, 2014)

- Deutsches Ärzteblatt (German Medical Journal) – various articles on spiritual and energetic medicine

- Journal of Religion and Health – peer-reviewed articles on spiritual aspects of healing